Nuclear weapons owe their existence to UC Berkeley.

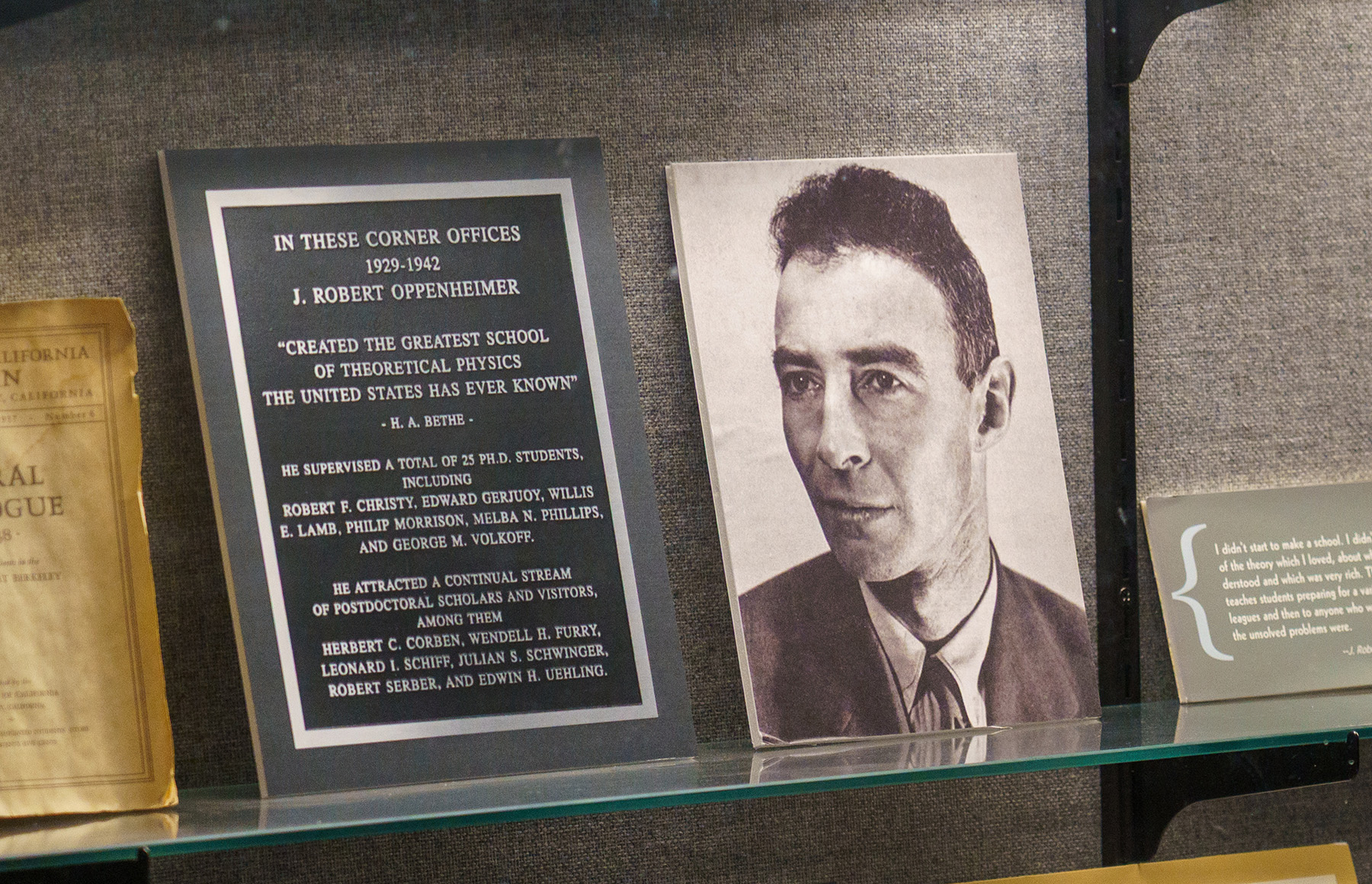

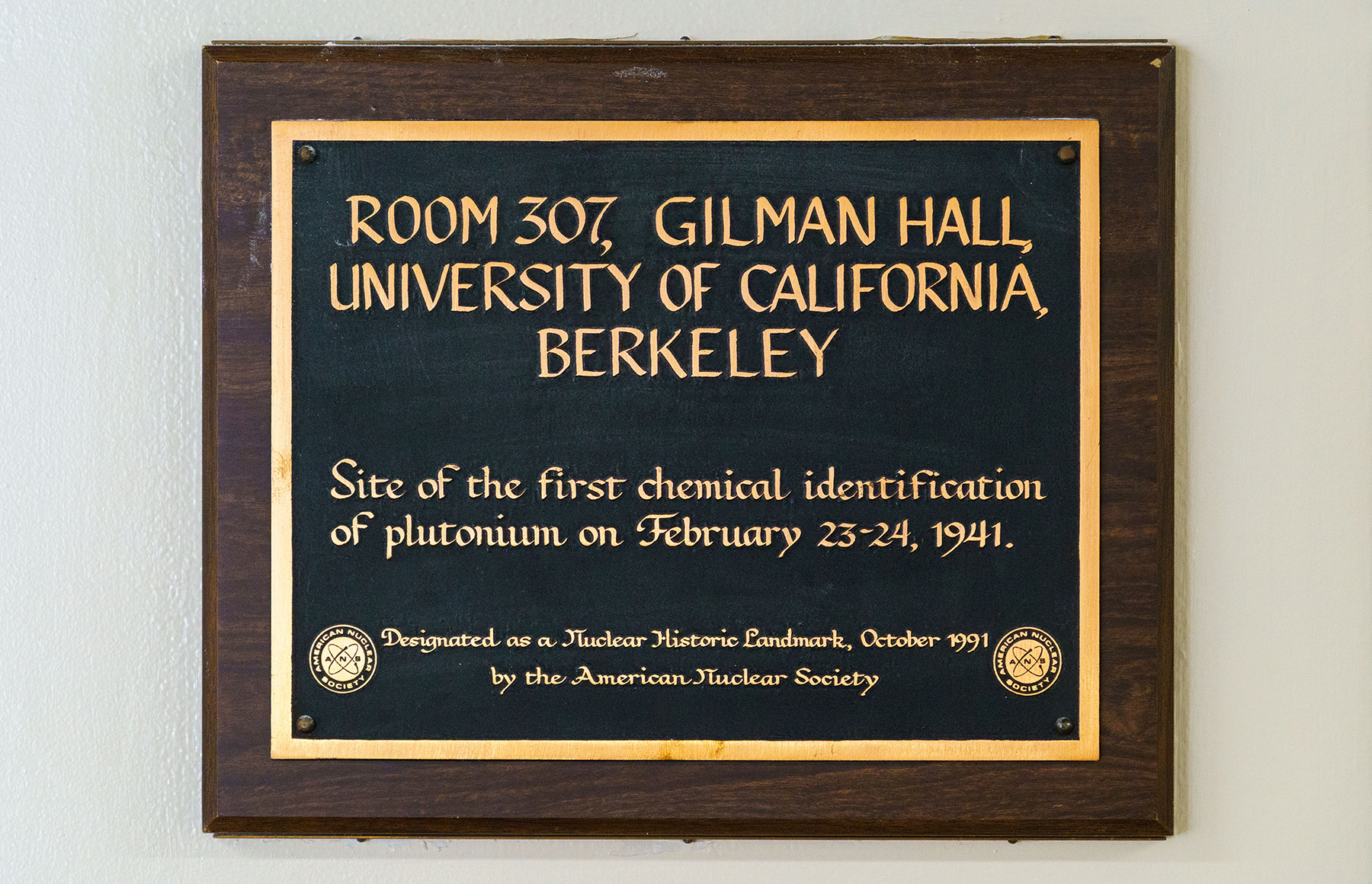

Plutonium was first discovered on campus in 1940. Five years later, the United States killed more than 75,000 people in Nagasaki with a plutonium bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” grew the theoretical physics department on campus and went on to manage the Manhattan Project at UC-affiliated Los Alamos National Laboratory.

In the years that followed, the city of Berkeley moved in the opposite direction, as a large-scale movement reacted against campus’s role in developing nuclear weapons.

In June of 1982, in the middle of the Cold War, 1,300 people were arrested at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. In the months preceding the June demonstration, four other protests occurred, resulting in a total of 500 people being arrested, including UC Berkeley faculty, students and staff.

At the time, the group “UC Faculty and Friends” called on the university to “no longer acquiesce with death,” in a statement to The Daily Californian.

Around Berkeley, vestiges of this opposition can best be seen in faded “Nuclear Free Zone” signs posted at the city’s borders. Such signs beg the question: What does it really mean for a city to be entirely nuclear-free?

The 1986 Nuclear Free Berkeley Act constituted a complete ban on the city doing business with nuclear weapons manufacturers or housing nuclear reactors within its bounds.

Now, UC Berkeley’s Nuclear is Clean Energy, or NiCE, is seeking to overturn the ban in a proposed 2026 ballot measure.

The group aims to incentivize the younger generation to get involved in the pro-nuclear energy movement — whether by helping to organize a 4/20 rave to “legalize” nuclear energy or standing in line near the Cheese Board Collective gathering signatures.

As the proposed ballot measure has not yet garnered opposition, the first battle is simply getting people to care. So does the fear of nuclear energy haunt Berkeley? It’s been 50 years since California voters enacted a landmark moratorium on the construction of new nuclear power plants, and nuclear research has advanced since — but has public opinion?

Berkeley: A nuclear-free city

The Nuclear Free Berkeley Act is a statement against nuclear proliferation, and among other provisions, it prohibits people, corporations and universities from “knowingly engag(ing) in work for nuclear weapons” and the city from entering into contracts with individuals or businesses who produce such weapons.

“Berkeley is already a prime target in the event of a nuclear war, and because the continuing arms race increases the likelihood of nuclear war, fear of such a war directly endangers our health and safety,” the act reads. “Children are especially frightened, depressed and disturbed by having to face the threat of extinction each day.”

The act prohibits the operation or building of nuclear reactors in the city. Two years after the act was passed, a nuclear research reactor housed in the basement of Etcheverry Hall was closed.

Still, the UC-affiliated Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory currently serves as the “lead design agency for three warhead systems currently active in the U.S. nuclear stockpile.”

Although most of the act was limited to nuclear weaponry, modern research seems to outpace some of the prohibitions. For example, facilities made to irradiate food with radioactive isotopes are also prohibited from operating within the city, despite the fact that the process, which is used to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life, has been endorsed by both the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the act was passed, there have been numerous attempts to repeal or amend the nuclear-free designation. In 2018, City Councilmember Gordon Wozniak wanted to overturn parts of the act that banned the city from investing in U.S. Treasury bonds, notes and bills, as reported by SF Gate.

A ‘new movement’ of nuclear energy in Berkeley

Now, NiCE needs more than 2,500 signatures from Berkeley voters to place their amendment to the city’s nuclear ban on the November ballot.

If the group is able to gather enough signatures — they’ve collected approximately 1,000 as of publication time — voters will be able to decide if they want nuclear energy, medical research and development in Berkeley.

The amendment would also remove the signs that mark the city as a “Nuclear Free Zone,” leaving only one remaining as an artifact in the Berkeley Historical Society and Museum.

“Nothing is a nuclear-free zone … There’s no part of our lives that there’s an absence of radiation in, and the human body and all living things are adapted to radiation,” said nuclear energy advocate Ryan Pickering. “So let’s be real. Let’s tell the truth. Instead of promoting fear, how can we promote knowledge?”

Pickering, who NiCE club members described as a “good friend,” is the Head of Development at Oppenheimer Energy, a nuclear project developer founded by J. Robert Oppenheimer’s grandson.

NiCE members made it clear that their advocacy for nuclear energy did not translate to support for nuclear weapons. Although both harness nuclear fission, nuclear weapons and reactors have fundamentally different designs.

It’s difficult to square Berkeley’s history and campus’s affiliation with modern warhead systems with NiCE’s mission to destigmatize nuclear power.

But for NiCE, Berkeley’s future is nuclear. They hope that passing this legislation in Berkeley could open the floodgates to nuclear energy in California, a state with only one remaining operating nuclear power plant.

“The purpose of petitions like these might seem small to some people, but how can we ever get the legislation to change?” said NiCE member and campus student Val Garcia. “For example, with the ban on constructing new nuclear (plants) in California, how can we ever (reverse) that if we still don’t allow for nuclear research in Berkeley?”

In some ways, it’s symbolic for a city that so strongly condemned nuclear development to definitively historicize its ban and pave the way for nuclear energy.