In late January, I attended a solidarity demonstration on campus for those experiencing state repression in Iran. Protests began in Tehran and quickly spread nationwide in late December, when the Iranian rial plummeted in value amid an ongoing economic crisis. Iranian authorities pursued a brutal crackdown on demonstrators, resulting in thousands killed or detained.

Prior to the event, I received an email from the Iranian Students Cultural Organization, or ISCO, communicating the intentions behind the gathering. “This is not a political protest,” the email said, followed by a list of guidelines for attendees. Despite the organizers’ request that people refrain from “inflammatory messaging” and focus on expressing solidarity with the Iranian people, the tone of the demonstration quickly changed when a man standing directly behind me called out, in Persian, “Death to Khamenei.”

I stood around for long enough to watch the organizers be upstaged by other members of the Iranian community, who led the demonstration for several minutes as they condemned Iran’s theocratic supreme leader. Holding up the former national flag of Iran, they chanted popular protest slogans: “Until the mullah is buried, this homeland will not be a homeland”; “Reza Shah, rest in peace”; and “Javid Shah” (long live the king). These chants, commonplace on the streets of Iran, allude to the 1979 dethroning of the former Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and the subsequent creation of the Islamic Republic. In addition to Persian-language slogans, demonstrators chanted “free Iran” and “regime change now.”

This episode may be considered a helpful case study of the Iranian diaspora today: the most organized and outspoken Iranians living abroad also happen to be those with the most reactionary politics. Many Iranians in the diaspora — and in Iran, too — support the former crown prince of Iran, Reza Pahlavi, in his latest bid for power.

Pahlavi and his supporters in the diaspora tend to suggest that Iranians have no other choice than to be liberated through Western intervention and, according to some, the restoration of the monarchy. This rescue fantasy seems founded both in nostalgia for pre-revolutionary Iran and in a kind of collective amnesia, an inability to recognize that the revolution in 1979 was not carried out by outside agitators, but by Iranians themselves.

The problem with nostalgia — and the warped vision of history required to sustain it — is that it can only ever be palliative, a means of smoothing out contradictions and heterogeneity within a population. Nostalgia is a fundamental component of nationalism, which, in this case, offers an imaginary solution to the distressing realities of exile while also making itself available for use in imperialist rhetoric.

I am thinking specifically of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s remarks during the 12-day war between Iran and Israel, his framing of the Israeli military campaign as an opportunity to overthrow the Islamic regime from within. “I know that Iran can be great again,” he said in a direct appeal to Iranians last June. He has also alluded to Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, which hasn’t existed for more than 2,000 years. For us in the diaspora to indulge this fantasy of foreign rescue and the restoration of pre-Islamic Iran is to deny that Iranians today possess any agency. It is an anesthetic, an attempt to alleviate the shame and trauma of a failed revolution.

“We’re not here as politicians, nor to advance an agenda,” one organizer stated at the demonstration on Jan. 27. Simply put, members of the diaspora cannot speak for those inside Iran, meaning that solidarity is often the most we can offer. It’s also worth noting that ISCO, per its constitution, is a “nonpartisan and inclusive” space, which prevents its leadership from organizing meaningfully through existing channels (not to mention the disparate political views contained within such an organization). At the same time, I found myself wishing that we did have an agenda, or that we could at least make some kind of gesture against foreign intervention and sanctions in the tradition of the Iranian student activists who came before us.

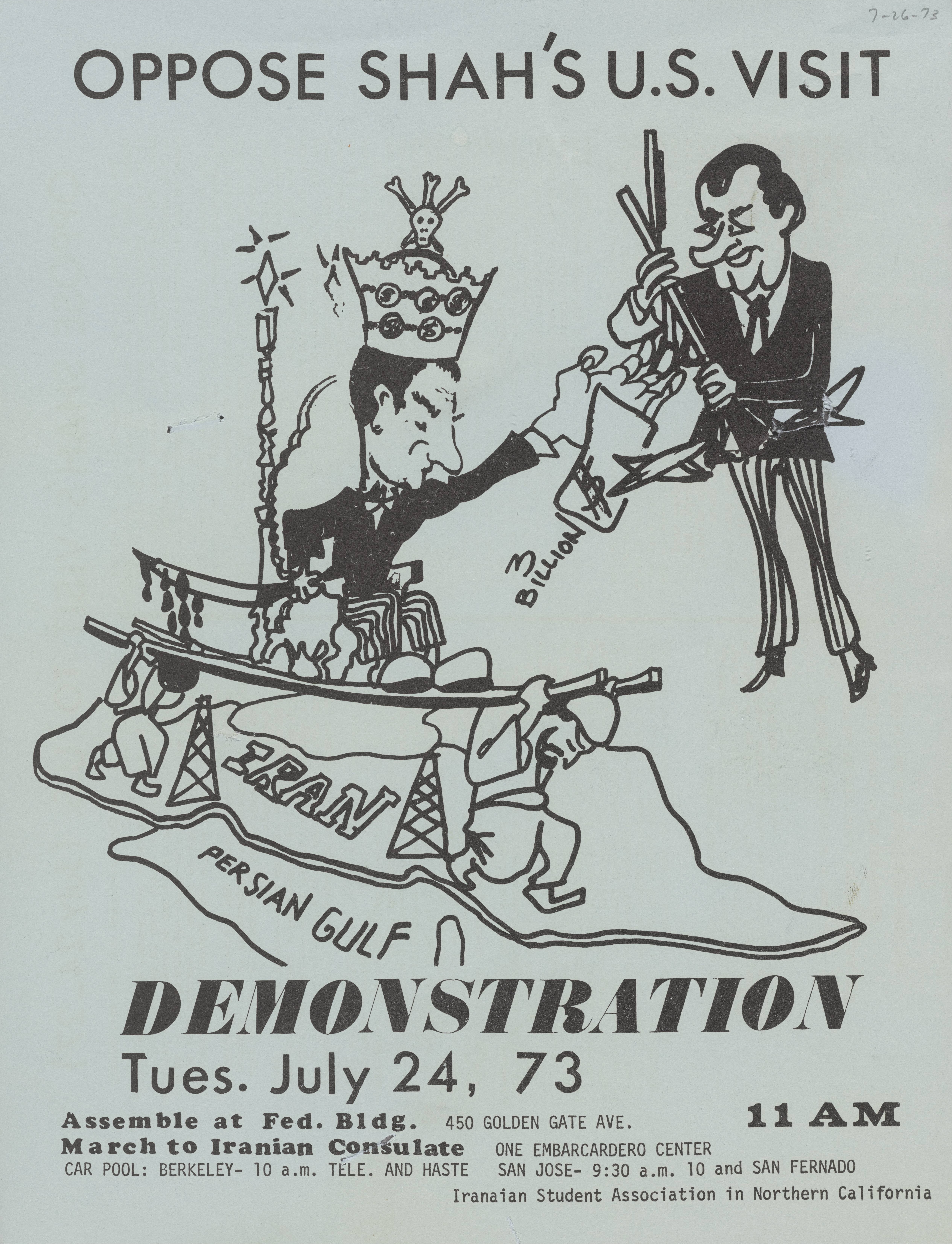

In the years leading up to the revolution, the Iranian Student Association in the United States (ISAUS, or ISA) worked to bring attention to the state violence committed against Iranians under the former Shah. They organized demonstrations to protest the Shah’s government and demanded an end to US interference abroad.

On June 26, 1970, 41 Iranian students occupied the Iranian consulate in San Francisco to protest the incarceration of political activists, striking workers and ethnic minorities in Iran. UC Berkeley ethnic studies professor Ida Yalzadeh offers an in-depth account of the incident, its aftermath and what it meant for Iranian racial formation at the time in her contribution to "American-Iranian Dialogues," a 2022 anthology edited by Matthew K. Shannon.

The 41 students were arrested by the Tactical Squad of the San Francisco Police Department and later charged with “conspiracy, burglary, false imprisonment, assault with a deadly weapon against a police officer, and malicious mischief,” according to Yalzadeh.

Several days after the 41 were arrested, another student demonstration took place near the Iranian consulate. KPIX-TV footage of the demonstration shows protesters holding signs that read “Down with the Shah,” “Power to the People” and “Support the Just Struggle of the 41 Students.”

Meanwhile, the Berkeley-based ISA chapter sent a letter to The Daily Cal’s “Ice Box” column, laying out their demands: that those incarcerated in Iran be released, that the protesters held in a San Francisco city jail be released and that Iranian international students be able to return to Iran without fear of persecution for their opposition to the Shah. They claimed that the protesters jailed in San Francisco were being “harrassed by the Immigration Office,” adding that the “Immigration Office has threatened to deport them.”

At the end of the letter, the ISA asks “all the progressive forces to join us in our struggles for the release of our brothers and sisters.” According to Yalzadeh, members of Black, Arab and Asian student groups were reported to have marched in support for the 41 at a major demonstration in San Francisco on July 1, 1970.

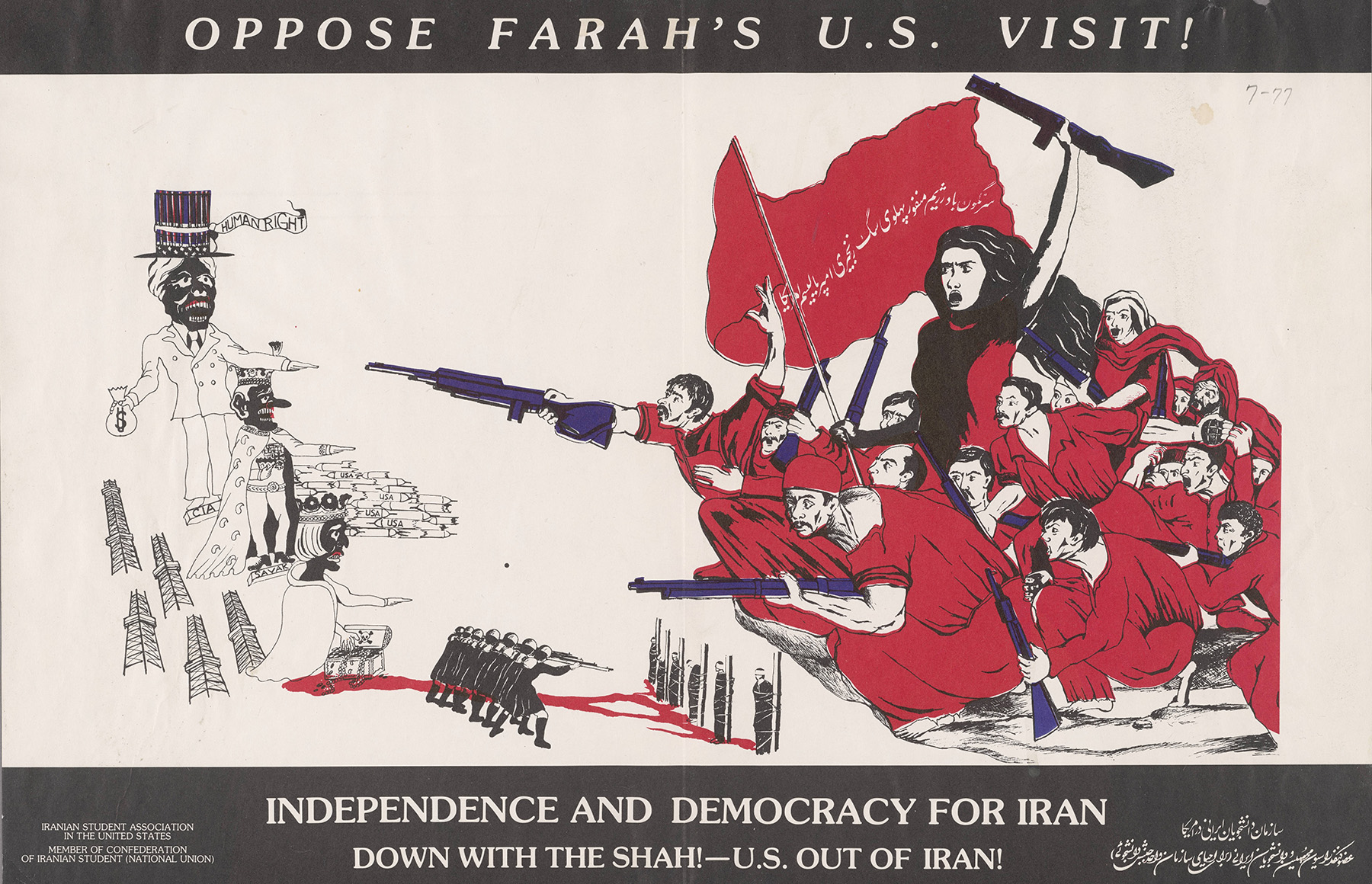

The successful appeal to the Bay Area’s “progressive forces” suggests that, against the backdrop of the Third Worldist and anti-war movements of the 1960s and ’70s, the ISA understood their activism as part of a broader international struggle. While the ISA distributed fliers and displayed banners denouncing the Shah as a “puppet of US imperialism,” they also collaborated with other left-wing groups in Berkeley such as the Vietnamese and Filipino student unions to host educational forums and film screenings.

The ISA’s solidarity with local communities of color, as well as their support for workers’ rights and the Kurdish freedom struggle, feel entirely absent from Iranian student groups that protest on university campuses today. Like the 41, there are Iranians currently facing deportation from the United States who would be persecuted in Iran for their sexual orientation, religion or political beliefs. Advocacy for the Iranian people should include demonstrating against ICE and the Trump administration’s recent crackdown on immigration — that is, being more like the ISA by standing in solidarity with other minority groups.

In case you couldn’t tell, I’m not immune to nostalgia either. There are obvious reasons why the activism of Iranian Americans of my generation bears little resemblance to the ISA’s work in the ’70s. For one, the United States no longer enjoys a neocolonial relationship with Iran, which makes it impossible to demand that American institutions withdraw support for the current regime. And while the ISA was portrayed in local media as a fringe group — communist “invaders” whose actions undermined not just the Shah’s efforts to modernize Iran, but democracy itself — those demanding a “regime change now” merely call upon existing US foreign policy.

In short, there is no going back. But when we remember the ISA, we manage to glimpse an alternative, unsentimental history of the Shah’s rule. The lesson is not to linger on the past, but to understand ourselves as part of a continuous struggle. “Independence and Democracy for Iran,” reads one ISA flier from 1977. It sounds exactly like what Iranians are fighting for now.

Supporting this fight as a member of the diaspora means insisting that the Iranian people are not a monolith, and that they have enough agency to determine their own future. It means protesting economic sanctions, which worsen Iranians’ standard of living more than they influence regime officials. It means opposing the Iranian government while also rejecting Pahlavi as the would-be figurehead of a revolutionary movement.

After the Shah was deposed in 1979, the ISA advertised a program at UC Berkeley for those interested in “the revolution in Iran” and “the political situation there.” The flier claims that the Iranian people’s gains toward “freedom, independence, and democracy” must be consolidated, and that the only way to achieve total victory is to rally behind Ayatollah Khomeini. “Neither US Nor USSR,” reads the flier, “Long Live Independent and Self-Reliant Iran.” One can look at the flier and conclude that these students were naive, idealistic, mistaken about what the revolution necessarily entailed. I look at it as proof of a certain revolutionary optimism, one that was co-opted and then extinguished by the Islamic state: hope for a future that never came to pass.

What I am nostalgic for, then, is the sense that things could be different; the desire not for things as they once were, but for something radically new. This is what the Iranian diaspora’s politics should aspire to.

The scene that I witnessed on campus several weeks ago happens to be a kind of echo, resembling moments during the recent protests in Iran. In an early account of the uprisings published by Feminists for Jina, the writer describes how dissent “spilled into the streets” of Tehran, followed by an internet blackout and the violent suppression of protesters. Mostly, though, they reproduce conversations that they had with fellow protesters about which slogans to use. According to the writer, many were chanting in support of Pahlavi, but could be compelled to change their tune. “Death to the dictator,” they eventually shouted instead. “Woman, life, freedom.”